Revised 01/21/2025

Listed below are some of our more noteworthy news articles concerning MABGA and our Junior Golf program. These articles include accomplishments from our active and previously active members.

In 2015, MABGA President Mario Tobia participated in five National and International golf tournaments. In June, accompanied by his coach and son Matt, they went to Mt. Kisco, NY to compete in the Guiding Eye Classic. Normally, that event is for the top 10 players in the US, but this year, the tournament committee invited Israel’s Zohar Sharon, the number one ranked player in the world. Mario finished in second place with a Stableford score of 49, the highest tournament score in the last 10 years and Mr. Tobia’s personal best. Unfortunately, Mr. Sharon scored 56 and won the event. In July of 2015, accompanied by his two sons, Matt and Michael, Mr. Tobia traveled to Milan, Italy to compete in the World Match Play Championship. This event matches the top four players in each sight category from North America with the top four players from the rest of the world. Mario won two of three matches, leading the North American team to the highest point getter on his squad. The Rest of the World team narrowly defeated the North Americans players in a very spirited and highly contested tournament. Later in July, accompanied by his teaching Pro and coach, Frank Hesson, Mr. Tobia traveled to Nova Scotia, Canada for the Nations Cup. This event matches the top 10 players from the United States with the top 10 players from Canada. The US team struggles and so did Mario and were soundly defeated by the Canadians. In August, again accompanied by his coach, Frank Hesson, Mario traveled to Marietta, Georgia to compete in the United States Blind Golf National championship held at the City Club Golf Course. Mr. Tobia took first place becoming a two-time USBGA national champion and retaining his number one ranking in the United States. Two months later, coached by Frank Hesson, Mario took second place in the American Blind Golf National Championship, narrowly losing to Phil Blackwell, a former world champion. That event was held on the Republic Golf Course in San Antonio, Texas. With those distinctions, Mario retains his number one ranking in the United States and is currently ranked fourth in the world.

In 2014, George Pilz. Another accomplished MABGA member. Took the low net honors in the USBGA Championship again held at Exeter Country Club in Exeter, Rhode Island, beating everyone in the field after adjusting his score by his handicap.

Other note worthy accomplishments include members who several years ago shot an eagle and three MABGA golfers who shot a hole in one. That’s right, three blind golfers who ace their shot on a par 3 hole. The first was recorded by Rod Ryan at the Meadowland Country Club on their 120 yard 14 hole on August 1, 2003. Larry Ruttenberg recorded the second hole in one at the 120-yard par-3 12th hole at the ACE Club in Lafayette Hill, and most recently, Sheila Drummond , a former MABGA member, shot her ace on the 144-yard, par-3 fourth hole at Mahoning Valley Country Club on Sunday, August 19, 2007.

Other articles are about the charity events attended by some of our blind golfers and coaches. Each event shares the common theme of helping the blind community and people in need. It is our pleasure to use our golfing talents to help make these worthwhile causes a success.

Update on Junior Golf Course on the grounds at New York Institute for Special Education

By NORMAN KRITZ, PAST JUNIOR MABGA CHAIRMAN.

November 22, 2020

This school for blind children is in the Bronx, NY. Two years ago they responded to the request to build a pitch and putt golf course on their campus. It took all that time to get where we are in November 2020.

As of today they have synthetic teeing areas for seven holes and a synthetic practice putting green with standard holes (4 1/4 inches). There is room for seven greens. The holes will be 8 inches. TWO Of the holes are wheelchair accessible. One of the holes has a SAND trap with a burm and one of the holes has a big rock in the middle of the green.

Fifteen years ago we had a junior member who was seven at the time (Kirk Brouwer). He has since graduated from Fordham University. his father Ken and a building contractor Dominic Parisi and I met at the school along with the executive director of the school (Bernadette Kappen). It has been a long hard road but we are seeing a light at the end of the tunnel. As you read this, the rest of the course is being built. Depending on the weather is when it will be finished.

The director of the Philadelphia Section PGA Geoff Surrette introduced me to the director of the NY Metropolitan Section PGA(Jeff Voorhees) and he contributed the labor and materials needed for the course. This included a real lawn mower (cuts greens) and the rest of the hardware needed.

I was lucky to have my son and our own Paris drive me to the Bronx, it is a 6 hour round trip. This was a labor of love and pictures will be forthcoming.

Blind golfers and sighted coaches welcomed at Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association

- By Catherine Nold Montgomery County Association for the Blind

- Jul 29, 2020 Updated Jul 29, 2020

More adults are continuing to enjoy golf even after losing their vision. The Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association (MABGA) is making it possible.

MABGA’s mission is to provide women, men and children who are blind or visually impaired the opportunity to enjoy the challenges and rewards that golf provides.

MABGA is a longstanding partner of the Montgomery County Association for the Blind (MCAB) that has two clients who are golfers with MABGA.

Serving blind golfers since 1948, MABGA has 110 totally blind and visually impaired golfers and sighted coaches ranging in age from late 20s to mid-80s.

Adult members participate in approximately 35 golf outings each year, as well as one special outing with a local PGA professional as a partner and an annual fundraising charity tournament.

At the 2020 season-opening golf outing in June at the Stonewall Country Club, Suzanne Woodall and Shawn Britt, both clients of MCAB, joined 16 blind fellow golfers for a day on the beautifully manicured course in East Nantmeal Township, Chester County.

Woodall of Hatfield, Montgomery County, just started taking lessons and playing in golf outings with MABGA this season.

“My fellow golfers are nice people and very competitive,” she said. “The outings get me out of the house onto some beautiful and exclusive courses. It’s really fun!”

Britt of Limerick became legally blind just over two years ago.

“The game and camaraderie makes me feel part of something,” Britt said. “I’m around people who have similar challenges to myself. I enjoy the socializing and the game. It’s a good feeling.”

Many golfers who lose their sight later in life think their golfing days are over. Not so, says Mario Tobia, president MABGA.

“I had been an avid golfer before losing my sight,” Tobia said. “At that time, I worried that my golfing days were over.”

Tobia joined MABGA in 2000 and began a whole new golfing experience. In the past 20 years, he achieved great success as a blind golfer, including being the top U.S. ranked blind golfer six times, and he finished fourth in the world twice.

“The main emphasis for people joining MABGA is both social and therapeutic,” Tobia said. “It is an opportunity to get out in the fresh air and socialize with your peers who are experiencing the same joys and challenges in life as you are. It’s like nothing you’ve ever experienced.”

Alan Test is a disabled, legally blind retired Vietnam veteran who presently serves on the Board of Governors and is the membership chairperson.

“I joined MABGA about four years ago,” he said. “Not knowing much about golf or the organization, I found a great group of people who include both legally blind or totally blind members. They are all willing to go out of their way to make you feel comfortable with the organization.”

Whether you’re new to golf or a seasoned golfer, it’s easy to give MABGA a trial run. Potential new members are invited to two outings initially to give them an idea of what MABGA is all about.

Each member must have a sighted coach with them at every outing, after which the member is invited to join for $100, the cost of annual membership.

MABGA plays more than 35 courses a year, and all outings and lunches are included in that one-time fee. The only additional monetary commitment requested is participation in the annual invitational golf outing, which has an entrance fee.

MABGA coaches are volunteers and are given the opportunity to play at all outings with a member team, at no charge. Lunch is included.

“We are always in need of more coaches,” Test said.

Coaches have golf experience but aren’t necessarily experts. They just have the desire to get out and experience life with a blind or visually impaired golfer. MABGA expects coaches to attend at least three outings per season.

To join MABGA, blind golfers must live in Philadelphia or its suburbs, South Jersey, Delaware and the surrounding area. All of the golf outings are hosted by golf courses within those areas. Coaches provide the transportation to and from the courses.

For membership information, to become a coach or to donate, send an email inquiry to info@mabga.org, call MABGA at 215-745-2323 or visit the website mabga.org.

MABGA is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation.

Annual Blind Golf Tournament Projected to Raise $100K for Children

By John Salazar | Spectrum News San Antonio

PUBLISHED 8:00 AM CT Oct. 17, 2019

SAN ANTONIO — Texans this week celebrated White Cane Day. The day, this year observed on October 15, acknowledges the abilities and contributions of the blind.

- American Blind Golf National Championship Tournament held Wednesday in San Antonio

- Event raises money for San Antonio Lighthouse’s Blind Children organization

- Winner is Canada’s Doug Penner

It additionally promotes equal opportunity and awareness of how the blind and visually impaired can live and work independently.

On Wednesday, golfers from the United States, Canada, Scotland, and England gathered to compete in the American Blind Golf National Championship Tournament.

Golfers, including Mario Tobia, from New Jersey, attended in order to raise money for the Blind Children’s organization at San Antonio Lighthouse.

It was anticipated the event would raise more than $100,000.

Blind golfers use guides to help them to navigate the course and tee up the ball.

Tobia began to go blind when he was in his 20s and he is now completely without vision.

“You just have to overcome that and put yourself out there,” he said. “You can’t give in to disability.”

Now in its 11th year, the tournament has so far raised $1 million. This year’s winner, Canadian Doug Penner, show a 140 over two days.

Giving it their best shot

With help from coaches, visually impaired golfers score success on the links.

By Natalie Pompilio FOR THE INQUIRER

Posted September 15, 2019

More than a decade ago, Dave Zimmaro was working at a golf club during college when one of the club’s certified PGA instructors casually mentioned that his next student was blind and that they’d connected through the Junior Blind Golf Association (JBGA).

“I was, ‘Stop — are you kidding me? Blind people can’t play golf. C’mon,’ ” recalled Zimmaro, 33, now the youth golf director at Villanova’s Overbrook Golf Club. “I thought it was all an elaborate joke.”

Then Zimmaro saw teenager Patrick Molloy, blind since birth, send a drive soaring with a left-handed swing so smooth that it had once been compared to World Golf Hall of Famer Phil Mickelson’s.

“He hit it and I said, ‘No way,’ ” Zimmaro said. “I didn’t know what this [organization] was, but I wanted to be a part of it.” That’s how Zimmaro became a coach for the JBGA, which partners blind or visually impaired young people with a PGA teacher for regular lessons. The nonprofit provides all of the necessary equipment for free — including the golf clubs — to participants, who are ages 7 to 21 and live in the tristate area. The lessons are provided at a golf course close to the participants’ homes.

On this sunny September Saturday, Zimmaro was hosting JBGA players and coaches at Overbrook, putting them into foursomes with sighted students from his youth program. Each young player had a parent along to play or to cheer.

“To watch these kids play and see the way they love it is a revelation,” said Norman Kritz, who cofounded the JBGA in 1993, was its longtime program director, and who, at age 90, is still committed to the cause. “We’ve had so many kids involved, about 75 right now, and it’s very gratifying. It’s important that parents of physically challenged kids know there’s something out there for them.”

The day before the event, Zimmaro had surprised his sighted golf students by declaring it “Overcoming Adversity Day.” He challenged them to take a shot with their eyes closed, then while sitting in a wheelchair, and then as if they were missing a limb. He also put obstacles in their way on the course, like forcing them to play balls that had landed in a sand trap or rough terrain.

Ali Gildea, 13, said most of the students “whiffed it” when they took a swing without sight.

“I had one decent shot, but most of my shots were pretty bad,” she said. “It was hard.”

That was the point Zimmaro wanted to drive home for his students.

“They gain perspective, and it builds toughness, perseverance,” he said. “I put pictures of students “with different physical challenges] at each [tee], and some of the kids were in tears, like, ‘How do they do that?’ They had no awareness that something like this even exists.”

Mike Molloy, Patrick’s father and current JBGA program director, organizes at least one group outing per month. This was a return trip to Overbrook, a pristine course with rolling green hills.

New JBGA students start with small swings. Some coaches will put a metronome behind a hole so the player can hit toward the sound.

“It’s all about building that muscle memory,” Mike Molloy said. “I don’t think Patrick took a full swing for months.”

Patrick Molloy, now 26, began taking lessons with a JBGA volunteer coach when he was 8 and continued to play golf through college. He said it’s the perfect sport for a blind person.

“As long as you have a coach who’s lined you up properly and taught you how to swing, you’re always going to find the ball,” he said. “You don’t have to see the ball in order to hit it. In fact, that’s a mistake that sighted golfers make: They’ll hit their shot and then lift their heads to watch that beautiful drive soar 300-plus yards down the fairway — but as soon as you lift your head, you lift your body and mess up the shot.

“As a blind golfer, you keep your head down, swing through and your coach tells you exactly where your ball went.”

Paris Sterrett, a coach for the JBGA and for adult members of the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association, agreed, adding that “70% of being successful in golf is how you line up, and you have to line up whether you’re blind or not.

“Your alignment, your stance is so important. Where you put your feet, where you place the ball,” said Sterrett, 77, who also coaches junior varsity golf at Episcopal Academy. “If you’re off just a little bit, that can affect the whole shot.”

Sterrett has coached golfers of all ages. There was the 5-year-old who slept with the trophy he’d won, and the 8-year-old who gave Sterrett a big hug after his first lesson. There were the ORFs (Old Retired Farts — like Sterrett) and octogenarians, like the 89-year-old who hit his first and only hole-in-one on a par-three hole that was 120 yards away, open on the front and with a ravine on the left.

“I lined him up, and he took a swing,” Sterrett said of that momentous shot in 2003. “He’d been playing golf for 65 years. It made national news.”

On this recent Saturday, Sterrett was coaching Leah Mullaly, 27, a legally blind golfer with whom he’s worked since she was 9. Mike Sullivan and his 9-yearold son, Jack, both of Wayne, rounded out the foursome. It was Mullaly’s turn to take a shot.

“We’re going to walk off the putt,” Sterrett said as he and Mullaly, who was holding his elbow, walked and counted the paces between the cup and Mullaly’s ball.

“I get 27 feet and it’s uphill,” he told her. “Jack says it’s going to break right to left — Jack knows these things.”

Sterrett helped Mullaly find her stance. She swung, sending the ball to the left of the hole.

“Nice swing,” Jack said.

Mullaly smiled.

“I don’t think Jack really knows that I can’t see that well,” she later said of her young fellow golfer. “He doesn’t know that I don’t know where the ball goes.”

The foursome playing in front of Mullaly’s group included Ali Gildea and her mom, Mary, club members from Bryn Mawr, and Tim Hengst, 13, and his dad, Sean, from Gloucester Township, N.J. Ali and Tim connected immediately over how they’d soon start eighth grade. Strangers when the game began, the players were each other’s biggest cheerleaders by the second hole.

Tim, who is legally blind, is a very enthusiastic golfer and is even teaching his father to play.

The weak point in his dad’s game? His form.

“He loses his balance a lot,” Tim said. “It’s hilarious.”

His father agreed. “It’s true. I’m terrible. When I swing I do this weird step thing,” he said. “Tim sets me straight, and when I listen to him, I get better.”

The Gildeas and the Hengsts won the four-hole “scramble” game. Tim took his trophy to a family party later that day.

But winning wasn’t the best part of the day.

“The trophy was nice, but he really had a fun time playing with Mary and Ali,” Sean Hengst said. “Before we even got the trophy, he told me what a good time he’d had and how he’d felt like part of a team.”

‘You don’t have to see it to tee it’ — Meet blind golf champion Mario Tobia

Updated 1557 GMT (2357 HKT) January 23, 201 – CNN

Story highlights

- Mario Tobia, 62, has progressively lost his sight over 25 years

- In golf, with the help of his coach, he has found salvation

- Now a national champion, he credits the sport with saving his life

- Mario Tobia (Mount Laurel, N.J.) – Corcoran Cup – 41 points

- David Meador (Nashville, Tenn.) – Cribari Trophy (second place) – 39 points

- Jim Baker (Nashville, Tenn.) – McFarland Trophy (most points over quota) – 21 points

- Ron Derry (Baltimore, Ohio) – Spoonster Trophy (most points over 2012) – 5 points

(CNN) — You approach the tee, select your club, adjust your hands, align your feet and visualize your swing.

It’s a routine practiced by millions of golfers around the world. Now imagine doing it with your eyes closed. All the time.

That’s what it’s like for Mario Tobia, a four-time American blind golf champion redefining what’s possible on the course.

“When I first lost my vision it was pretty traumatic,” Tobia tells CNN Sport. “I had to stop working and things like that.

“Now I actually tell people that golf saved my life.”

Blind golfer Mario Tobia stands confidently on the golf course alongside his sighted coach, Frank Hesson, who provides guidance and support. Together, they exemplify the power of teamwork, determination, and adaptability, proving that “you don’t have to see it to tee it.” Their partnership highlights the possibilities of adaptive sports, breaking down barriers and inspiring others to pursue their passions regardless of challenges.

A Hands-on approach

Tobia regularly drives the ball over 240 yards — just 50 yards less than the PGA Tour average.

Typically scoring in the high 90s and low 100s in a casual round, the New Jersey native has shot as low as 86.

But, of course, he doesn’t do it all alone.

Enter Frank Hesson, a golf coach with a difference.

“I’m Mario’s guide,” says Hesson. “Usually we’ll get out to a golf course, go through a warm up program, just like anyone else would.

“Mario knows through his own practice how far he hits the ball with each of his golf clubs. Basically, he relies on me to give him some lie conditions.

“When he’s ready, I grab the club and set it physically behind the golf ball. I tell him to open or close the club face, depending on whether it’s lined up correctly.

“And then he says ‘good?’ and I say ‘good!’ and he goes off and takes the shot just like everybody else.”

Muscle memory

It’s moments like that which provide Tobia temporary escapism from his blindness — brought on over the course of 25 years with a degenerative condition called Retinitis Pigmentosa.

“Blind golf gave me a goal and something I wanted to accomplish,” he says. “With the help of my kids I started improving my game and, as time went on, I started seeking professional assistance with coaches like Frank.

“It’s really changed my life and given me something to look forward to.”

While Tobia might not be able to gaze up at the trajectory of his ball, or watch as it rolls into the cup, the satisfaction of a sweetly-struck shot is a feeling shared by both player and coach.

“Wherever his ball lands, it’s my job to visualize that,” Hesson explains. “Some of the other players and other coaches look at us with their mouths wide open, but it’s just something that he and I do together and both enjoy doing.

“And it kind of crosses the Ts and dots the Is for us on the putting green.”

“Putting has always been a strength of mine, and I’ve retained that, even through losing my sight,” says Tobia.

“Of course, I rely heavily on Frank now for the direction, and he takes care of the breaks and speed. But if we call it a 10-step putt, I know exactly how hard I have to swing for the ball to go 10 steps.

“Frank will make an adjustment and, if the green is a little downhill, he’ll say ‘putt it nine steps.’ I’ve really got to trust that when I swing, the ball will be there. It’s all about muscle memory.”

“We have a funny anecdote,” says Hesson. “When he makes a long one, I say ‘it’s all coach, it’s all coach!'”

Real-time feedback

Technology has also come to Tobia’s assistance in the form of the K-Vest, a wearable device that provides provide real-time audio and visual feedback on the golfer’s posture and swing.

Training through feel, Tobia can work on his game from the comfort of his own home.

“The learning curve is so much quicker,” he explains. “One of the biggest problems I have is Frank and I will work on something but then I won’t see him for a week or so.

“I have a net in my backyard and a platform in front of it, all lined up. But when I practice there, I have no feedback from Frank, so before it wasn’t uncommon for me to be out of sync with the motion all wrong by the time we next meet up.

“Now I get that feedback in real time. I could be in Pennsylvania and he could be in South Jersey, and we can still be communicating and doing the work.”

Walking the fairways

The duo can cause quite the stir among the unacquainted out on the fairways and greens.

Tobia recounts a particular round where he played with the aid of his son, Matt.

Defying his condition even more markedly than usual, the blind golfer made par or bogey on almost every hole, “going around pretty quick.”

All of a sudden, after hitting something of a rough patch, Tobia became aware of some commotion between his son and the group behind them on the course.

“The guy behind us was saying we were taking too much time,” Tobia recalls. “It had been the first hole we’d actually played slow. I said, ‘let’s go back there and I can explain what’s going on.’

“I say to the guy: ‘We apologize, but I’m blind.’

“All of a sudden he realizes what has been going on. He was seeing my son lining me up for every shot, walking the steps with me and presuming I was having lessons out on the course.

“He had no idea I was blind … sometimes people just don’t know.”

A ‘wonderful’ journey

Such stories are testament to the levels Tobia and Hesson have been able to achieve, proving “you don’t have to see it to tee it,” as the The United States Blind Golf Association motto proclaims.

Having finished fourth in the world two years ago in Japan, they’re now eying up top spot at the upcoming Blind Golf World Championships in Rome.

“I was born in Italy and I have a lot of family there, so that’s my goal,” says Tobia. “What a great honor it would be to win my first World Championship in the place of my birth.”

What a great journey it has already been for the 62-year-old, who could have quite easily walked away from sport forever when he first received his diagnosis.

Looking back now, what would Tobia say to others around the world that are facing similar afflictions?

“For me, it would be to keep on living,” he says. “Find something that interests you; find something that you enjoy doing and got out and do it.

“For me, that’s the best advice I can give to somebody. Don’t succumb to blindness, stay home and pity yourself.

“Put yourself out there and just see what happens. Good things will happen. I’ve met a lot of great people, including Frank who I probably wouldn’t have met.

“I wouldn’t have played at these international tournaments had I not lost my sight. It’s been wonderful.”

To the next hole at the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association event

by Scott Anderson / For the Burlington County Times

Posted April 29, 2017

Mount Laurel’s Mario Tobia (left) and his coach Frank Hesson, of Medford Lakes, return to their golf cart at the Medford Lakes Country Club on Thursday, April 27, 2017, during a golf outing of the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association.

Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association to hold tournament April 27

9-hole tournament to be held at Medford Lakes Country Club

by Chris Franklin, Medford Sun

Posted on April 26, 2017

On Thursday, April 27, the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association (MABGA) is holding a golf opportunity for visually impaired individuals. The event will be a 9-hole golf tournament followed by a luncheon for participants.

The upcoming event will be hosted by Medford Lakes Country Club, located in Medford Lakes.

“We are thrilled to host this event for the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association,” said Rob Mondelli, general manager of the country club. “It’s especially exciting for our club and members as our assistant golf pro, Frank Hesson, is the coach for Mario Tobia, one of the best golfers in the country.”

MABGA was formed in 1948, and for over 68 years has been assisting both junior and adult individuals with the sport of golf. Each blind golfer is paired with a volunteer coach who performs as a mentor throughout the golf season. Participants are welcome and can be paired with blind golfer and coach. Spectators are encouraged to come out to the country club and cheer the golfers on.

For more information is available at both www.mabga.org. Interested people can also send an email to the Medford Lakes Country Club at gm@medfordlakescountryclub.com.

Barrington boy gets vision back

Kim Mulford , @CP_KimMulford

Published 1:18 p.m. ET March 31, 2017 | Updated 12:04 p.m. ET April 5, 2017

Barrington resident Jon Paul Corman, 9, who is legally blind, acclimates to his new pair of eSight eGlasses Thursday, March 30, 2017 in Philadelphia.

PHILADELPHIA – John Paul Corman tried on his new high-tech glasses Thursday and had just one word to say: “Wow!”

In front of the third-grader’s eyes was a set of eSight Eyewear: a camera, a powerful computer and LED screens that help legally blind people see images in real time. As a company representative showed him how to use the technology, Jon Paul gazed around the hotel meeting room, swiveling his head to see his mother’s face, a laptop, a camera.

There was a lot to take in.

After the Courier-Post chronicled his family’s $15,000 fundraising campaign in December, donations poured in from local Lions Clubs and other civic organizations, individuals and anonymous donors to help the 9-year-old get his own pair. Within 10 weeks, the campaign raised more than $12,000 toward the cost of the glasses – and then the company dropped the price for the latest, lighter version to $10,000. The extra money was given to help buy eyewear for another user.

“It was a lot of people who came together,” marveled his mother, Faye Corman, who sent thank-you notes to every donor she could identify. “Every little bit helped.”

Jon Paul could only see light when he was adopted at age 3 from China. After corrective surgery and glasses, the third-grader could see colors and shapes, and read very large print. He uses a cane to help him get around and is learning how to read Braille. After an eSight demonstration last summer, the boy bugged his parents repeatedly to get him his own set.

“Are we bringing the eSight home?” Jon Paul asked from beneath the eyewear, half whispering to his mother.

“Yes, of course,” she told him. “It’s yours, forever and ever.”

The eSight Eyewear processes images from a live video stream and delivers them in real time onto LED screens in front of the user’s field of vision. The headset captures whatever the user is looking at, whether it’s a printed book or a person across the room or at something far away.

The Toronto-based company began selling the headwear in 2013; it has sold a couple hundred since then.

Fascinated by electronic devices – and elevators – Jon Paul played with the eyewear’s controls, quickly figuring out how to zoom in and out, focus on objects, take pictures and turn on its handy flashlight. The set can connect with a computer to play videos. The first one Jon Paul asked to see was “Toy Story.”

Brandon Leibgott, an eSight representative, was impressed with how easily the child adapted to the eyewear.

“It’s working like a charm for him,” Leibgott said. “This will be an extension of himself, because it’s bionic vision. Like someone who uses a wheelchair and it becomes the way they move around, it will be the way he sees. He’s going to see through video in his life. It will allow him to see more than he ever could otherwise.”

Corman said she couldn’t wait to take Jon Paul to the zoo, so he could finally see the animals.

“Right now,” Corman said, “he thinks it’s just a hot place that smells bad.”

Kim Mulford: (856) 486-2448; kmulford@gannettnj.com

Building for the blind

by Greg Norman, www.golfcourseindustry.com

Posted: October 2016

Preliminary sketches provided by Norman Kritz for a nine-hole golf course and practice putting green at the Maryland School for the Blind. No hole on the proposed course exceeds 60 yards.

KRITZ is a Philadelphia-area pharmacist. Charitable involvement turned him into a golf course architect. His first – and still only -completed project resulted in a playable course for blind children.

More than 500 satisfied players later, Kritz could be moving toward repeating what the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association constructed at Overbrook School for the Blind. “It’s been a revelation,” ByGuy Kritz says. “It’s the greatest thing I have ever done. Just watching the kids play is a reward in itself. We would like to build a golf course for every school for the blind.”

The nine-hole course at Overbrook School for The Blind opened in 1996. Programs conducted at the course receive help from numerous industry efforts, including the GCBAA Foundation Sticks for Kids.

The Overbrook course, in a densely populated northwest Philadelphia neighborhood, opened in 1996, three years after the MABGA started its junior program. With help from maintenance crews at Cobbs Creek Golf Club and Bala Golf Club, the MABGA constructed a golf course, with no holes longer than 45 yards. Holes were designed around a quarter- mile macadam track, making the course wheelchair accessible. The facility took two years to build.

Along the way, the MABGA has received help from numerous Philadelphia-area golfers and pros who volunteer time to offer instruction and services such as resizing and regriping donated clubs. The junior program received a boost when it established a relationship with the GCBAA Foundation Sticks for Kids program. Kritz, who directs the MABGA’s junior programs, drove from Philadelphia to Jersey City, N.J., in early August to attend the annual GCBAA Foundation auction and raffle. Kritz mingled with GCBAA members and gave a passionate presentation about how support from efforts like Sticks for Kids help blind children. Sticks for Kids provides the MABGA with clubs, bags and other equipment.

“Sometimes you take it for granted when you are in the national offices, and you see letters and emails keeping us posted on what programs are doing and how you can help them” CCSAA executive directof Justin Apel says. “And then you get a chance to have someone like Norman come and shows us the pictures and teil us the stories. It’s indescribable, not only to us as staff, but to our members.”

An encounter at the GCBAA meeting could help Kritz accomplish his goal of designing another course for blind children. Chris Hill, the President of Georgia-based Course Grafters, has committed to offering his company’s expertise when work starts at a site in Macon, Ga. No timetable has been established for the project, but Kritz is eager to work with a professional golf course builder.

“It will be a teaming experience for me,” he says. “I’m a pharmacist, been a pharmacist for 65 years, so building golf courses is totally foreign to me. We are not creating Pebble Beach or Pine Valley. It’s something that these kids can do and they seem to love it. As long as they have smiles on their face, I know I’m doing a good job.”

Kritz also has completed preliminary sketches for a nine-hole course and putting green at the Maryland School for the Blind. Multiple holes on the Maryland course will be wheelchair accessible.

The programs at Overbrook are models for other blind schools that build golf courses. On the first Saturday this fall, a junior event attracted 32 participants and 40 volunteers. Participants are taught a variety of golf and life skills, including the importance of caring for the coarse. Overbrook’s grounds crew handles maintenance, and local superintendents make themselves available when needed. Functionality, though, is the most important factor when building and maintaining a course for blind golfers.

“I don’t think the greens [at Overbrook] would come in at 12′ on the Stimpmeter,” Kritz says. “They are puttable. Let’s put it like that. We just had a clinic and 32 kids were there. I didn’t have any complaints, so I figured it must be good.”

Tom and Peg Harrington

Peg and Tom Harrington hold a photo from their wedding day on May 1, 1948, as they approach their 66th wedding anniversary.

By Jennifer Connor, The Reporter

Posted: 03/10/14, 7:59 PM EDT

When asked what the secret to a long and successful marriage is, 87-year-old Tom Harrington, shakes his head.

After being married to his wife Peg for nearly 66 years, Tom says there is no secret.

“It’s simply about being considerate of each other,” Tom said. “We always had strong communication and worked together as a team.”

Coordinating their efforts was necessary in order to raise their 10 children — nine of whom were boys.

“I never minded having all those children,” Peg said, starting to laugh. “But, I do despise cooking. I was so glad when they came out with instant potatoes.”

Peg said some of her go-to meals included hot dogs and baked beans and spaghetti and meatballs, though she emphasized that she does love baking her specialties of chocolate chip cookies and brownies.

Peg and Tom met in high school at a Christmas party — Tom a senior and Peg a junior. Though they grew up in the same zip code, they never met before, in part because Tom went to the all-boys Catholic school St. Joseph’s Prep and Peg attended the all-girls school Mount St. Joseph’s.

“I thought he had a great sense of humor and he loved to dance,” Peg said. They began going to the weekly dances at Holy Child in Philadelphia and have been dancing ever since.

Peg said some of her favorite memories with her husband include dancing to Tommy Dorsey’s “Boogie Woogie.”

When Tom graduated high school in 1943 he attended St. Mary’s College of Maryland where he enrolled in the naval officer program, which transferred him to Penn State for a semester and then to Villanova to finish his program. While at Penn State, the Navy took over all of the fraternity houses near Rec Hall. Tom lived in the Phi Delta Theta house. Upon graduating officers school, Tom served in the Navy from 1945-48. He never saw direct combat, but his service took him from Pearl Harbor, across the Pacific Ocean as far as Japan. When he came home on breaks, he and Peg would go out — usually dancing. After his service, he moved in with his parents, and he was in her parents’ living room when he asked Peg to marry him.

They married on May 1, 1948, in a formal wedding service at Little Flower Parish in Mount Airy.

The second of four girls, Peg was the third to wear the same wedding dress as her sisters. Her mother handmade the bridesmaids’ dresses and hats. Tom and Peg spent a week at Split Rock Lodge in the Poconos for their honeymoon then moved in together in Abington.

When their only daughter and oldest child Marti was born, Peg left work to raise her children, who are — in order from oldest to youngest — Marti, Tommy, Jay, Richard, Tim, Greg, Beau (Robert), Andrew, David and their youngest (and Lansdale resident) Stephen.

The hardest part of their marriage was the loss of three of their children.

They lost Jay at age 7 to nephritis, a disease that causes inflammation of the kidneys.

Their son Tommy also tragically died during his senior year of high school as a passenger in an automobile accident.

Richard, at the age of 52, lost his life to a brain aneurism.

“It was hard to experience each of those losses,” Peg said. “But all of our children were and are marvelous.”

Today, to keep busy, Tom plays golf — even though he is legally blind.

About 20 years ago, macular degeneration along with glaucoma caused severe vision loss in both of Tom’s eyes. He joined the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association where he just became the acting president. The group of 32 players — 22 men and 10 women — 15 of whom are completely blind, play about 35 games in their season from April to October.

Coaches, who can see, direct them on the course; Tom says they could always use more coaches. (To learn more visit www.mabga.org.)

Peg stays busy catching up on the phone with her children, 13 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, and continuing to bake.

“I think truly we are really great friends that are very fortunate to still have each other,” Peg said.

If you are a part of or know of a couple who has been together for many years and would like to share your story, contact Jennifer Connor at jconnor@thereporteronline.com or on Twitter @Journalist_Jen.

Giving the Gift of Golf to Blind youth

By Sandy and Gil Kayson, Community contributor

The organization has grown a lot since being founded in 1994.

In 1994, a new world was created for children and Young adults ages five to twenty-one who were Visually impaired or blind. Due to the vision and determination of Gil Kayson, a blind golfer, his wife, Sandy, and their dear friend, Norman Kritz, a sighted golfer, visually impaired and blind children and young adults can now learn and participate in the Wonderful game of golf.

The story begins with the creation of the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association (MABGA) in 1948. A blind lawyer and Golfer named Robert Allman had the desire to share the joys of golf with his blind friends. His dream was to organize competitive Golf within the blind community. This dream became a reality when a small group of blind golfers started playing rounds of golf every Sunday at the Juniata Golf Club in Philadelphia, With the help of Joe Hunsberger, golf professional and his assistants. In 1949, Bob Allman’s friend, Francis Strawbridge, Jr, was elected as the organization’s first president. For the next three decades, MABGA continued to thrive, reaching out to hundreds of blind golfers in the Delaware Valley and beyond.

Then, in 1980, Gil Kayson, a blind businessperson, sports enthusiast, learned about the association. Several years passed and Kayson continued to enjoy the game of golf while making many new friends, both sighted and blind. One of these friends, Norman Kritz, a sighted golfer had experience building chip and putt golf courses for troubled youth. Driven by their passion for the game of golf combined with their love of children, Kayson and Kritz, along with Kayson’s wife, Sandy, shared a vision to create a junior golf program for blind children to learn and play golf. Jim Ganter, an active MABGA member who later became president, was very much interested in the program and instrumental in helping it get started.

Ganter, Kritz and the Kayson’s all agreed that they wanted to have a golf course specially built and designed to meet the challenges of visually impaired and blind golfers. However, there were many obstacles that they had to overcome to accomplish their goal. First, they needed to find a suitable location.

In addition, the resources to make their vision a reality. Kritz’s children, an architect, and a landscape architect, agreed to generously donate their time and expertise to help design the golf course. Kayson and Kritz reached out to the Overbrook School for the Blind and soon their vision would become a reality. The Overbrook School agreed to donate land on its campus that would become the future site for a golf course dedicated to the Junior Blind Golf program of the MABGA. Under the direction of Norman Kritz and his children, the custodial staff at the Overbrook School would change the campus forever. Everyone worked diligently and finally, on Sept. 25, 1996 the Robert G. Allman golf course was dedicated to the Junior Blind Golf Program.

With the completion of the course, the group now turned their focus to reaching out to the visually impaired and blind community to apprise them of the wonderful development. Flyers went out to blind schools and blind organizations looking to recruit young golfers. At the same time, they began to seek out golf professionals who would volunteer to teach the children how to play golf. Al Balukas, a golf professional and mentor for MABGA agreed to help find the golf professionals for the children.

Fifteen children contacted them and the Junior Blind Golf Program was under way. Now, the organization was faced with one final challenge. They needed to obtain equipment to enable the children to play the game. The children would need properly sized golf clubs and shoes. Kritz worked diligently to obtain donations of golf equipment. Donated golf clubs would be cut down and sized specially to fit each child. Every child provided his or her age, height and whether it were right or left-handed to insure the clubs were properly measured. Each child received his or her own customized free set of clubs, shoes and a glove. The parents provided the names and addresses of five golf courses closest to their home so Al Balukas could find a volunteer professional to teach the visually impaired/blind child how to play golf.

The golf professionals were eager to participate in this wonderful program. The parents then had to contact the assigned golf professional to schedule a convenient time for their children’s lessons. The association encouraged the parents that golf, different from other sports, was a game that their child could play for a lifetime. With the parents’ guidance and support, their children would be given the opportunity to enjoy a sport for life while making many new friends along the way. And furthermore, the Junior Golf Program, with continued support of the MABGA, would provide their children this incredible opportunity at no cost.

With the golf lessons having begun, the Junior Blind Golf Program held its first golf clinic and outing in the spring of 1997, bringing together visually impaired/blind children and their families to enjoy a wonderful day of golf. There, the children and their families would make new friends and celebrate their accomplishments. They shared smiles and stories and learn that with some persistence and dedication, they too can enjoy the excitement of playing the game of golf. Since the program’s inception, golf clinics and outings are held twice each year, in the spring and the fall. A volunteer golf coach is assigned to assist and guide each child on the course. With the help of a group of dedicated volunteers led by Sandy Kayson, the outings have been a tremendous success. Each event concludes with a wonderful luncheon for the entire family, and trophies and prizes to recognize the participants’ achievements. Since its inception, participation in the program has continued to grow, reaching hundreds of children and their families over the years from many states including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, New York and Maryland who attend the outings in addition, take private lessons from golf professionals. Recently, children from as far as North Carolina and Colorado have joined the program as well.

What makes the Junior Golf Program especially successful has been its ability to attract visually impaired/blind children with diverse interests and backgrounds, which are brought together for one common goal, to be able to learn and play the game of golf while making new friends for life. With this unified focus, these children are taught the important values of commitment, dedication and perseverance, which will serve them well not only in the game of golf, but also in every endeavor that they will pursue throughout their lives.

One does not have to look far to see some of the incredible successes of the Junior Blind Golf Program. Brian Mackey, a participant in the program for several years just completed his First year in the adult program of the MABGA and currently serves as a mentor and an assistant golf coach in the Junior Program. Another young man Patrick Molloy, who started as a Junior Blind Golfer when he was seven years old is now in his junior year at Muhlenberg College. Molloy plans on attending law school upon graduation to pursue a career in law. Another graduate of the program, Casey Burkhardt, received his master’s degree from Villanova University and is currently working for Google. Jon Gabry, a deaf-blind junior golfer and an artist, is the poster child for the Helen Keller National Center? Gabry has been selling his art work in both New Jersey and New York and currently has four pieces on display in the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. The parents of these children have expressed that their children’s participation in the golf program has helped give them the confidence to pursue their dreams. The program has also served as the inspiration for the authoring of the book, “A Million Dollar Putt,” written by Dan Gutman. Gutman specifically acknowledges the work of the year’s outings.

Another success of the program occurred two years ago when Kritz and Kayson were approached by the First Tee organization in Philadelphia. This organization has a program that teaches children (not blind) how to play golf. First Tee thought it would be wonderful if the Junior Blind Golfers could play golf with the First Tee members. The idea was approved. In addition, this past year six outings were held at the Walnut Lane golf course in Philadelphia.

These outings proved to be a huge success for all. This “learning by teaching” experience provides the children an invaluable experience that they can draw upon throughout their lives. The collaboration demonstrated to sighted children, not just what blind children could accomplish, but also what other physically challenged children are capable of achieving.

Perhaps the program’s most exciting news in 2013 came when they were contacted by Steve McWilliams, a film producer and writer, who works in the disabilities office of Villanova University. McWilliams is in the final stages of the creation of a documentary featuring the story of the development and success of MABGA’s Junior Blind Golf Program.

To create the documentary, Steve McWilliams and his staff attended an outing, where he interviewed Kayson, Kritz and the junior blind golfers and filmed the children playing golf. The hope is that this documentary will heighten the awareness of the Junior Golf Program, while serving as an inspiration to others to help expand the opportunity for visually impaired/blind children to other cities across the country. It has been an incredible journey thus far for The Junior Blind Golf Program. The founders, officers and volunteers of this program encourage parents, relatives, friends and teachers of visually impaired or blind children to make this a priority and spread the word. The dream is that many more children can take advantage of all that this program has to offer. For more information on the organization visit www.mabga.org/junior-golf or call Gil Kayson at 215-884-6589.

Mario Tobia wins Corcoran Cup during Guiding Eyes for the Blind Golf Classic at Mount Kisco

10 June 2013, 9:16 am

<

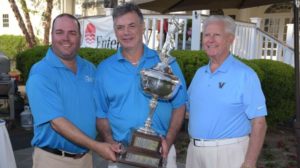

Photo courtesy of Guiding Eyes for the Blind – Mario Tobia (left) won the 2013 Corcoran Cup, coached by son Matthew Tobia, with Guiding Eyes for the Blind’s Golf Classic Chairman Al Maiolo.

Guiding Eyes for the Blind Corcoran Cup At Mount Kisco C.C.

Founded by PGA legend Ken Venturi in 1977, the Guiding Eyes Golf Classic has raised over $8 million since its inception. As part of the Classic, Guiding Eyes presents the Corcoran Cup, the “Masters” of blind golf. This year thirteen of the country’s top blind golfers vied for the coveted trophy, each with the help of a coach who aids in club selection, alignment, setup and distances.

Blind golfer wins ‘Most Courageous Athelete of The Year Award

BY MARK KRAM, Daily News Staff Writer

kramm@phillynews.com

Posted: January 29, 2013

MARIO TOBIA was 25 when a doctor diagnosed him with retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye disease that would leave him blind. The doctor told him that by age 30 he would have night blindness; by 40 he would no longer be able to drive; and by 50 he would have to walk with a cane. The doctor told him to begin preparations for a future without the ability to see.

It was devastating news. Tobia could not bring himself believe it. Surely, he told himself, there was some error in his diagnosis, that perhaps the problems he had been having picking up the ball off the bat in his softball games were due to something else. So Tobia did not prepare himself as the doctor recommended, only to discover that his prognosis had been correct. With each passing year, his vision continued to dwindle until it vanished completely and left him steeped in darkness.

Given his disability, a golf course seemed an unlikely place to find Tobia, who is now 57. But that is exactly where you can find him. Tobia not only still plays golf but plays it so well that he was bestowed with 2013 Most Courageous Athlete Award by the Philadelphia Sports Writers Association Monday evening at its 109th annual dinner at the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Cherry Hill. Joined by his wife, Ann and their two adult sons, Matt and Michael, Tobia characterized the plaque he received as “a tremendous honor for me.”

“I was humbled to even be considered for it,” says Tobia, who lives in Mount Laurel, N.J. “When I heard who some of the previous winners had been, I was just blown away by it.”

Tobia began playing golf at age 30, in part because his deteriorating vision prohibited him from participating in any sports that involved hand-eye coordination. At Cinnaminson High School, he had competed in football and track and field. He won a partial scholarship to La Salle to throw the discus. Golf enabled him to continue to compete until he could no longer see the targets on the course. It was not until he discovered the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association in 2000 that he began playing again. Nationally, he has competed in events with the U.S. Blind Golf Association and the American Blind Golf Association. He has won four ABGA and USBGA events the past 2 years, including the 2010 ABGA championship in the Blind Division. Although he shoots in “the mid-90s to 100,” he says his goal is to shoot in the 70s at some point.

How does he do it?

With the help of his two sons and a coach, Steve Rodos.

“We guide him by the arm,” says son Michael. “We line him, let know how far he has to hit and then describe where it has landed.”

“Like a caddie would do,” adds the other son, Matt. We help him analyze the shot he has to play.”

Says Rodos: “Like any golfer, he has to stay out of the woods. Of course, he has no idea where the woods are.”

Tobia says his sons helped him simplify his swing. “When I could see, I had a swing with a lot of movement in it, a swing that required a lot of hand-eye coordination to get back to the ball,” says the former computer consultant who now teaches visually impaired and blind veterans in South Jersey and Delaware to use computers. “So we had to shorten up and find a swing I can rely on.”

Michael says putting is a challenge: “At one point, when he still had some vision, one of us would stand behind the pin and he could see our outline. Now, what he will do is walk off the distance between the ball and the cup. By doing that, he can also get a feel for how the green is leaning.”

Ann Tobia says her husband was “very involved with their sons when they were growing up. When it came to golf, he taught them everything he knew. Now, they are giving back to him.”

Does Tobia consider what he has done courageous?

He pauses before he says: “I think of it more as survival than courage,” he says. “Golf has given me a chance to get out of the house and socialize with people.”

Tobia recommended that to “anyone with a handicap. Regardless of what it is, you just have to find something you enjoy doing,” he says. “And then take on the challenge. Get out and play a sport or join an organization.”

Tobia said he is at peace with his affliction. “Ten years ago, when I still had some sight, I would dwell on the fact that I could no longer see as well as I once could. Now, I feel better about myself than I did then.”

So how good is he?

Good enough to fool some fellow golfers out on the course, according to his son.

“People will look at us on the course and sense something is unusual,” Matt says. “This is usually four or five holes [into play]. When I tell them he is blind, they just look at him and say, ‘He plays better than me.’ “

No sight, no problem for Mount Laurel golfer- Courier Post

Written by Randy Miller, Courier-Post Staff

Posted: 12:27 AM, Sep. 4, 2012

Local blind golfer refuses to stop teeing off: Mario Tobia needs a lot of help, but he’s one of the top blind golfers in the nation.

EVESHAM — A green golf cart with a white roof zips down a path toward the 18th tee at Indian Spring Country Club, slowing down only to negotiate water puddles left from afternoon showers.

When arriving, a well-tanned 57-year-old who was born in Italy and moved to South Jersey at age 1 hops out from the passenger seat and walks to the back of the cart.

Mario Tobia fiddles with his golf bag for a few seconds, pulls a white Titleist ball from a side pocket, grabs his Ping G20 driver from a compartment and waits for his coach to provide first a helping hand and then instruction.

Steve Rodos, a 75-year-old retired Philadelphia attorney who seems to get around like he’s 60, grabs Mario by the arm, then together they walk to the second tee from the back, the white one that’s for men.

Staring down at his iPhone, which has a golf GPS app called up, Steve announces that the flag is 482 yards from the tee.

Mario nods, takes a big practice swing, then inches forward toward his teed-up ball.

Steve, dressed in shorts, a golf shirt and a baseball cap, moves in to carefully study Mario’s positioning and barks out a quick adjustment that results in a tiny leg shift. He backpedals until safely out of harm’s way, then leans forward and sets his hands on his knees.

Mario lets loose a sweet-looking swing, and when club and ball meet right where he had intended, that familiar pinging sound momentarily drowns out chirping birds.

The ball disappears into the overcast sky before dropping 230 yards from the tee in the middle of the fairway.

“OK, that was good,” Steve blurts out.

Mario needs to be told where his ball lands because his world is total darkness. He sees nothing out of his left eye and can only tell night from day with his right, and if the sun is shining brightly, he must wear sunglasses to avoid pain.

His slow deterioration toward total blindness forced the Mount Laurel resident to stop driving years ago and, beginning in 1995, left him unemployed for a time. But by sheer determination, this amazing man overcomes not being able to see in unimaginable ways.

For starters, here’s a fellow who will cook scrambled eggs on his stove for breakfast and hamburgers on his grill for lunch when Ann, his wife of 29 years, is working in Cherry Hill.

Mario now earns a living again, too, as a contracted computer technician who formats and repairs PCs for visually impaired and blind Veterans.

“I’m determined,” said Mario, who has a driver take him to and from Veterans homes in South Jersey and Delaware. “When I set my mind to something, I want to do it.”

His golf game is something special among peers. Locally, he dominates playing with sighted partners in 40 annual Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association tournaments. He’s even better playing on his own in United States Blind Golf Association (USBGA) and American Blind Golf (ABG) national events, finishing in the top three in six of seven tournaments over the last two years, winning three of them. He’s the two-time reigning champion in the American Blind Golf National Championship, held annually in San Antonio, and he’ll be back there again in October going for three in a row.

“He’s one of the top three in the country,” Steve boasted.

A coach to blind golfers isn’t a typical coach. What this volunteer job really amounts to is being the eyes of the golfer.

Steve “coaches” Mario at local events, while Mario’s two children – sons Matt, 28, and Michael, 23, – handle the national tourneys, which include trips to such places as Georgia, New York, Ohio and Texas.

Mario knows it won’t be easy, but his quest is to become a much better golfer. His handicap currently is 23.8, which means he’s a little shy of being a bogey golfer. He’s gotten this good despite mostly playing just once a week during the local season, but he’s far from satisfied.

“I want to be considered a good golfer … good for anybody,” Mario said. “That’s part of my drive. I do well in these tournaments against vision impaired or blind people, but I want to beat my kids.”

Matt, who has a Masters from Fordham and lives in Hoboken, is a 7 handicap. Michael, a recent graduate from Seton Hall who still lives with his parents, is a 10.

Matt recently talked Mario into switching from a conventional putter to a belly putter, after having some struggles in a recent national event in New York in which missing “4 or 5 makeable putts” resulted in a second-place finish instead of a victory.

The hardest part about being a blind golfer, Mario says, is chipping.

“Because it’s a feel thing,” he said. “When you take that half-shot or quarter-shot, that’s hard for me.”

Other parts of his game aren’t that difficult.

“I know generally how far my clubs go,” Mario said. “If it’s 150 yards to the hole, I’ll pull out a 7-iron because I know that club will go 150-155 yards. If I’m on the green, I walk it off.”

Mario is able to identify his 12 clubs by positioning different kinds of tape in different shaft positions. For instance, he uses hockey tape for his 5 and 6 irons, electrical tape for his 7, 8 and 9. Keeping certain clubs in certain compartments of his golf bag makes it easy for him to differentiate, as well.

Mario knows when he strikes the ball well, but needs to be told whether he hit it straight or not. Making good shots never gets old.

A year ago, Mario came within an inch of sinking a first hole-in-one on the 106-yard, 17th hole at Philmont Country Club in Huntington Valley, Pa., during an alternate-shot tournament in which he was paired with Patrick Shine, head pro for Commonwealth National Golf Club in Horsham, Pa.

“The very next hole, I had the exact same shot on my second shot, 106 yards to the pin,” Mario said. “I pulled the same club, a gap wedge, and made what I thought was the same swing. It sailed over the green 40 yards. We had to take a penalty stroke and ended up tying instead of winning.”

Like everyone, Patrick Shine is inspired by Mario, his partner the last five or six years in an area vision-impaired Pro Am.

“It has to be incredibly challenging for Mario, but he does a pretty good job and he’s totally into it,” Shine said. “He expects me to play well, and it’s a little bit of pressure because it’s like his Super Bowl and don’t want to let him down.”

Steve takes Mario by the arm after his tee shot on No. 18 at Indian Spring, then take their cart to the fairway, stopping a short walk to the left of the only ball nearby.

“We’re about 255 away,” Steve says, his iPhone again in hand.

“I can’t get there, so I’ll lay up to maybe 100 yards,” Mario responds while clutching his 7-iron.

They approach the ball. Steve backs up and goes into his hands-on-knees position. Practice swing. Whack.

“You pushed that to the right,” Steve says with a hint of disappointment in his voice. Steve pauses, then in a perkier tone says, “So we’ll go get it and hit from there.”

Mario, who is 6-foot-1, 210 pounds with a full head of dark hair, was 25 when he first noticed he was having eye issues. He’d been nearsighted, but contact lenses had corrected his vision to 20/15. He figured he just needed an another adjustment, and sure enough, an eye doctor examined him and prescribed stronger contacts.

The issue only worsened.

He’d always been a good athlete and played baseball, football, tennis, volleyball and ran track at Cinnaminson High School (Class of 1973), and after getting a degree in computers from LaSalle University, he was playing shortstop in an adult baseball league when noticing he was having all kinds of trouble picking up groundballs hit his way.

He started going to more doctors searching for answers. About the 10th one finally provided a diagnosis that was terrifying. His condition, a Pennsauken ophthalmologist determined, was Retinitis Pigmentosa, a degenerative eye disorder that affects 1/4000 Americans.

“You’re going to have trouble seeing when you’re 30, you’re going to have to stop driving when you’re 40 and you’re going to need a cane to walk when you’re 50,” Dr. Ralph Lanciano told Mario.

“Thirty-two years and a lot of a frustration later, Mario says, “He was almost dead on.”

Almost.

“Doctors told me for a long time that I wouldn’t lose all my sight, that I always would retain something,” he said. “I’m already past that point.”

Mario’s 50th birthday was bittersweet. On July 9, 2005, he and Ann went out for dinner at the Library 2 Restaurant in Voorhees. He still remembers there was a setting sun as they waited for Ann’s sister and her husband to arrive.

“I was right next to my wife facing her, and when I looked, I saw her perfectly,” Mario said. “And that was it. I’ve never seen anybody’s face since.”

For a time, Mario made out silhouettes of people, and even when he was first started being coached in blind tournaments a few years ago, he often could get a feel for where the pin was during putts by having his coach stand at the flag wearing white shoes to contrast the green grass.

There is no cure for Mario’s condition, but he gained hope right around his 50th birthday by qualifying for an experimental study at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. A chip placed into his left eye hopefully would regenerate retina growth.

“We felt like we’d won the lottery because to us it was something,” Ann said. “Mario just broke down and said, ‘All I want to do is watch my boys hit a baseball.’ He coached the boys when they were younger in basketball, coached them in baseball. He got involved in everything. When my boys were really little, he’d be outside at 6 in the morning putting in the backyard before he went off to work.”

The test not only failed, but that’s when Mario stopped being able to tell night from day in his left eye.

He took it hard.

Mario is dealing. He gets around his home well, often using walls to navigate, although he still has his share of falls even with a cane.

“When I leave a door open, I get in trouble,” Ann says. “He’ll walk into it. Nothing really lays around, but you know he’s going to trip. Every day I come home and wonder what black-and-blue mark he’s going to have for walking into something.”

Steve drives Mario to his ball again, this time for an approach shot.

“Here we are,” Steve said. “We’re 100 yards away. The pin is in the middle of the green.”

“Exactly 100 yards?” Mario asked.

“Exactly,” Steve says.

“What’s the front of the green?” Mario asks.

“The front of the green is 87,” Steve answers. “Put a nice swing on it and we’ll go tip it in for the birdie … or the worse, for the par.”

Mario pulls out a pitching wedge, then reaches down to get a feel for how damp the grass is.

“It’s wet,” Steve says.

“It’s going to take something off it,” Mario counters.

Mario takes his practice swing, gets lined up … whack.

“Little bit to the right,” Steve said.

The ball comes out of the air on the green, rolling to a stop about 35 feet to the right of the pin.

The toughest thing about being blind, Mario says, is losing his independence. As much as he does, he wants to do more. He misses driving and hates having to rely on someone to get somewhere.

A low point was when he stopped working for awhile at age 40.

“It was tough for a few years,” he said. “I had plans. I wanted to start my own business. Then, when I tried something, either I wasn’t good at it or people were not as helpful as I would have liked. People would say, ‘You’re blind, you can do telemarketing.’ I said, ‘That’s not what I want to do. I want to do more than that.’

“It’s not always been easy, but at some point you say, ‘I’m alive, I’m healthy except for my eyes. I can do stuff. I gotta find a world for me.’ You say this is no way of living, but you find a niche for yourself, and that is what I did.”

Just like when he was sighted, Mario works in computers, only now he uses computers and software that talk.

“When it comes to a PC, if you have anything that you need, that man can fix it,” his wife said. “He’s helped sighted and unsighted people. It’s pretty amazing. It really is.”

Mario pulls out the belly putter he’s still getting used to, walks with Steve up a little hill onto the green and then to the flag.

Mario taps the middle of the pole with his putter, making a clinging sound, then counts off steps until reaching his ball, again while holding Steve’s arm.

“So it’s 12 (steps) … up hill,” Mario says. “I’m sure it’s a little slow.”

Mario is led to his ball, gets lined up and asks, “Am I good?”

“Yeah,” Steve says.

“OK, 12 steps, up a hill,” Mario says to himself.

He adjusts his feet every so slightly, then gently makes contact. The ball rolls slowly toward the hole and looks good until curving a hair left and stopping 4 feet short.

Mario was born in 1955 in Teramo, Italy, which is 93 miles northeast of Rome on the Adriatic Coast, and he came to America a year later when his parents settled in Camden. His father worked as a tool and die maker, and young Mario quickly became bilingual, learning English and Italian.

Mario has returned to his homeland about 10 times since, the last visit coming last May with his sister. They visited two uncles for closure.

“We visited the Italian Riviera, a very scenic place on the ocean that I hadn’t been to before,” Mario said. “I could hear the waves from the sea and picture it. In my mind, I think I know what it looks like.”

Mario doesn’t ask for descriptions for people he’s met since becoming blind, and just the other day he mentioned that he has no idea what Steve looks like. Told by a third party that his coach resembles a young George Burns, Mario pictured the late comedic actor of a past generation in his mind, then nodded and said, “OK, OK.”

“I tell people I’m 6-4,” Steve counters. “Think Cary Grant!”

Another time, a friend once described two women in an unflattering fashion, which led Mario to chime in and say, “Don’t tell me that, you’re ruining it for me!”

The ball is a short putt from the hole.

“Little over a step (away),” Steve says.

Mario reaches an arm out and feels the flag, then grabs it and sets it down out of the way.

“OK, this is for the par,” Mario says. “Good golfers make this.”

Steve backs up, tells Mario to adjust a little to the right, then tells him “too much.” Another adjustment corrects that. Mario takes his time, putts and … the ball rolls slow and straight, then drops in.

Mario hears the familiar sound of a ball falling into a cup, and says, “There we go! Just a par!”

Golf didn’t become a big part of Mario’s life until he started losing his sight. He took it up at age 30 and over time it became a passion.

“There was a period of 4 or 5 years where I stopped playing altogether, after I stopped working for awhile,” Mario said. “It wasn’t until the found the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association around 2000 that I really start playing again.”

Mario and Steve, 18 years apart in age, have become close in their six years together on golf courses. Mario is greatly appreciative of the time and help, while Steve enjoys the company and admires everything Mario accomplishes on and off the course. Best of all, they have fun together.

Steve, who also is married with two sons, started volunteering a little prior to meeting Mario when showing up for an early golf outing and hearing coaches were needed that day for a blind outing.

A favorite story Steve tells of Mario is from when they were at their only national tournament together a few years ago in Edgmont, Pa. It was raining like the dickens and Mario just refused to take cover.

Mario persevered and ended up finishing third.

“I tell him all the time he’s the third-best coach in America,” Mario said.

To Ann Tobia, Mario is the No. 1 spouse, and despite how their lives have changed, some of their best times have come since he’s lost his sight.

“You know what?” she said. “We’re truly blessed, I have to tell you. With everything. Even though Mario has an issue, we have a great life. We really do.”

GOLFMount Laurel resident third i national tourney

By Phil Chappine Staff Writer | 0 comments

Posted on August 9, 2012

Mario Tobia hoped for a better finish this year.

The Mount Laurel resident competed in the United States Blind Golf Association national championship earlier this week. Tobia placed third among the 25 golfers in the field at Middle Bay County Club in Oceanside, N.Y.

Tobia totaled 47 points in the two-day tournament that uses the Stableford scoring system. That was one point behind the runner-up and 18 points behind champion David Meador.

“I was expecting to win,” Tobia said Thursday. “But to beat him (Meador), I would have had to play really well.”

Tobia improved upon his score, if not his finish, from last year. He was second with 44.25 points in 2011.

The USBGA championship is scheduled for 36 holes, 18 each day. Because of wet conditions on the Long Island course, this year’s tournament was limited to nine holes on the first day.

Tobia finished the first round with 13 points, then gladly accepted help from his coach, older son Matt Tobia. Michael Tobia also coaches his dad in some tournaments.

Golfers are accompanied by coaches, who “act as their eyes” (according to a USBGA news release). Matt saw some things that needed correction.

“I was not very good at all,” Mario said. “Matt watched my swing. After we finished the round, we went to a driving range and figured out what I was doing wrong. So I did better the next day, moving up from sixth place to third.”

Mario scored 34 points, second most on Day 2 (Meador scored 45).

“Overall, I was pleased because of the way I moved up,” Mario said. “I was disappointed that we only were able to play nine holes the first day. But it ended up being to my advantage, as poorly as I was playing. I would have been farther back. In hindsight, it benefitted me.”

Golfers competed in three categories. Tobia was one of 16 players in Class B1 (totally blind). He began to lose his sight in his early 40s due to retinitis pigmentosa. Classes B2 and B3 are for less visually impaired, the difference being degree of impairment.

No sight, no problem – Burlington County Times

Posted: Sunday, August 5, 2012 12:00 am | Updated: 9:02 am, Mon Aug 6, 2012.

By Dave Zangaro, Staff Writer

Mario Tobia had to quit his job.

He had to give up his license, too. His condition, retinitis pigmentosa, was slowly deteriorating his eyesight. Before, he was an athlete, a hard worker, a family man. He was only in his early 40s.

His life was changing for good, and there wasn’t a damn thing he could do about it.

That’s when he found refuge in a small white ball he could just about see.

Tobia, a Mount Laurel resident, is now 57. His eye condition has left him completely blind for several years. But he still finds refuge in that little white ball, even though he can’t see it at all anymore.

Tobia will compete in the 67th annual United States Blind Golf Association National Championship on Aug. 6-7 on Long Island, N.Y. Last year, he finished in second place, just four strokes behind the leader. This year, he wants to win.

“I certainly expect to place,” he said. “I hope to do better than that. I hope to win. I would be disappointed if I didn’t place.”

Tobia has always been a competitor. He was an athlete growing up. He played several sports at Cinnaminson High School. He even went to La Salle University on a track and field scholarship; he threw the discus.

But golf? That was for old guys.

“Old men play golf,” he said, remembering his old attitude with laughter now. “I guess one day I started to get old, because I started to play.”

But the real reason Tobia started to play was because his eyesight was starting to go in his early 30s. The sports he once played — basketball and tennis — became harder and harder. He could at least play golf.

But as his eyesight deteriorated further, he eventually had to give up driving — the only way he had to get to the course to play with his friends.

“I had a couple close calls driving,” Tobia said. “One scared the hell out of me. I was just lucky I didn’t hurt someone else or myself.”

Once he stopped driving, he left his job at a publishing company, too. He was at home trying to find a job suited for a blind person and there wasn’t too much available. To make matters worse, Tobia was stuck in his house. The day-to-day socialization of a normal life had followed his eyesight into nonexistence.

“When I stopped working,” he said, “that’s pretty much when I stopped playing golf.”

That’s when Tobia, in his 40s at the time, started attending support groups for visually impaired people. He hadn’t golfed in a few years, after he wasn’t able to drive.

But at one of the support group meetings, he heard someone mention golf for the visually impaired. Naturally, Tobia was interested, so he checked it out.

He joined the Middle Atlantic Blind Golf Association and began heading to several more-casual golf events. When he first joined the group, he had some of his vision left, which he said made it a little easier. He could still make out the ball — at the very least, he could see his target.

“He struggled at first. But he persevered,” said Tobia’s oldest son, Matt. “He’s a stubborn guy. It’s one of his strong qualities. He’s persevered. His game has gotten better and better. Great support group, a lot of camaraderie. We decided to take a chance.”

Matt, 28, and his younger brother, Michael, 22, have both been Tobia’s coach at several tournaments. Basically, they are now his eyes. Matt remembers his dad teaching him to play golf when he was just 12 or 13.

“His vision loss has always been there,” Matt Tobia said. “It’s not a handicap to our family. It’s the way it is. You tell other friends and family and they say, ‘I can’t believe that.’ We expect it. He’s an athlete. He competes.”

Golf has become a family game for the Tobias. And it’s not just because Mario can’t see. It gives the family a common bond, just like any other family. In fact, Tobia said his sons have become pretty good at the sport, much better than he ever was — with or without sight.

“I was hoping their genes would rub off on me,” he said laughing. “It hasn’t worked.”

Matt Tobia will be his father’s coach this week on Long Island. It will give father and son a chance to reunite. Matt no longer lives in South Jersey.

“I don’t cut him any slack,” said Matt, who added that Mike is the softy of the two.

There are different division for blind golfers: B1, B2 and B3. B1 is where Tobia plays. That’s the completely blind group. When he started golfing as a visually impaired person, he wasn’t a B1. And even after he was completely blind, he waited for a while before he joined the B1s because he wanted a challenge.

Tobia completely lost his sight about seven years ago. The last time he remembers seeing a face was at his 50th birthday party.